Iñupiat children follow their relatives around to learn fishing, hunting and other subsistence-related techniques critical for survival. The long winter months also give time for children to learn Iñupiat games. Some children play a fantasy game called “polar bear”, where one child plays the role of an old woman who falls asleep. The polar bear then comes and takes her child away. The woman wakes up and attempts to discover where the bear has hidden him/her.

In Utqiaġvik, children play a slightly different version of the same game called “old woman”. A young child plays the role of an old woman who pretends to be blind, and when several of her possessions are stolen, she “accuses” other children of taking them. This game requires a fair amount of verbal exchange and the more able the talker, the more likely the winner.

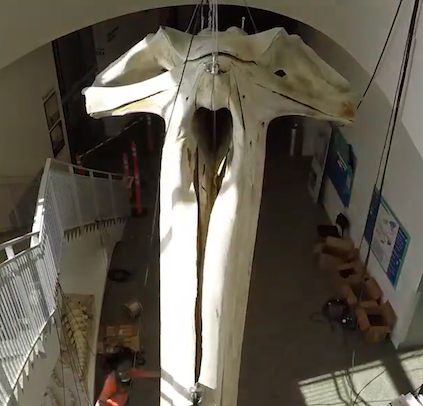

Did you know Point Lay went 72 years without harvesting a bowhead whale? In 2009, after fighting to get a quota from the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, the community landed their first bowhead since 1937. The successful Atkaan crew and its captain Julius Rexford dedicated the feast to Elder Dorcas Neokok, who had recently passed away, but was instrumental in passing on the oral history of bowhead hunting in Point Lay. The community was nearly abandoned after World War II but the Neakok’s remained and after the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 was signed, former residents began moving back. The community had historically been a part of spring whaling but their claim was questioned as they attempted to get a new quota for the village. Neakok provided stories and even letters from before the war telling her own stories of hauling meat and maktak to the village by dog sled. Finally, in 2008 Point Lay was recognized as a whaling community and given a quota, and it only took one year before the first whale in over seventy years was harvested.

Anaktuvuk Pass is home to the Nunamuit – people of the land – known to be the last nomadic group of Native Americans in North America. In the summer of 1949, families at nearby Killik River and Tulugak Lake came together and settled Anaktuvuk Pass. Elders like Elijah Kakiññaaq Kakinya would travel by foot and dog team through the Brooks Range up to the Beaufort Sea to hunt seals and other marine mammals. Residents would also travel to Flaxman Island and Beechey Point to hunt and trade with Iñupiats along the coast.

Today, people in Anaktuvuk Pass rely on the caribou migration just as their ancestors did, giving residents a sophisticated knowledge of caribou behavior and ecology. Historically, the Nunamuit used an array of hunting methods. They’d construct iñuksuits, human-like figures to direct or funnel caribou over many miles into corrals, lakes or rivers where hunters waited with spears, or bow and arrows.

Aluakpak is a historic coal mining site approximately 15 miles inland from Wainwright and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. After being introduced to iron stoves in the late nineteenth century, the area was used by residents of Wainwright to mine coal for their homes and the school. While driftwood provided an uncertain source of fuel for coastal communities, the interior villages and camps depended on coal instead.

Each fall, families moved from Wainwright up to the Kuk River to their fish camps and they would portage their equipment to Wainwright lagoon, then tow or sail their umiaqs to Aluakpak. From there, they would camp long enough to sack coal to haul to their family camps. Coal from Aluakpak was also occasionally used by passing ships, one of which contracted Waldo Bodfish of Wainwright to deliver sacked coal in time to meet the ship when it came up the Chukchi coast.

Kivgiq is a messenger feast filled with dancing, singing and traditional Iñupiaq foods. Historically, the event was hosted by a successful umialik (whaling captain) to celebrate an extremely good year of hunting. Runners were dispatched carrying messenger sticks, called ayauppiaq, to invite surrounding villages to the feast. The messenger sticks would have items attached to them to symbolize gifts the host wanted brought to him and to remind the carrier of his message. Kivgiq was also a time for trading between coastal and inland villages. In addition to these types of economic exchange, the interactions served to strengthen regional alliances, family connections and helped reaffirm trade partnerships.

Traditional Kivgiq’s have been celebrated for centuries and continue today, with the last traditional feast taking place in Wainwright in 1914.

In 1918, an Iñupiat named Ootoyuk, working with a former teacher named William V. Van Valin, conducted an ethnographic study in the area around Point Barrow. Ootoyuk reported finding human bones protruding from a mound of earth on the tundra about eight miles from Utqiaġvik. This mound and several others like it had previously been assumed to be weathered glacial deposits. But what Ootoyuk and Van Valin found instead were well-preserved skeletons of men, women and children, many still wrapped in skins and furs and accompanied by an assortment of tools and utensils.The artifacts Van Valin excavated are now attributed to the Birnirk Culture (A.D. 500-1000), which precedes the Thule Culture (A.D. 1000-1850) in the Barrow area and are considered to be the predecessors of modern Iñupiat.